- Blog Mawjoudin

- February 22, 2024

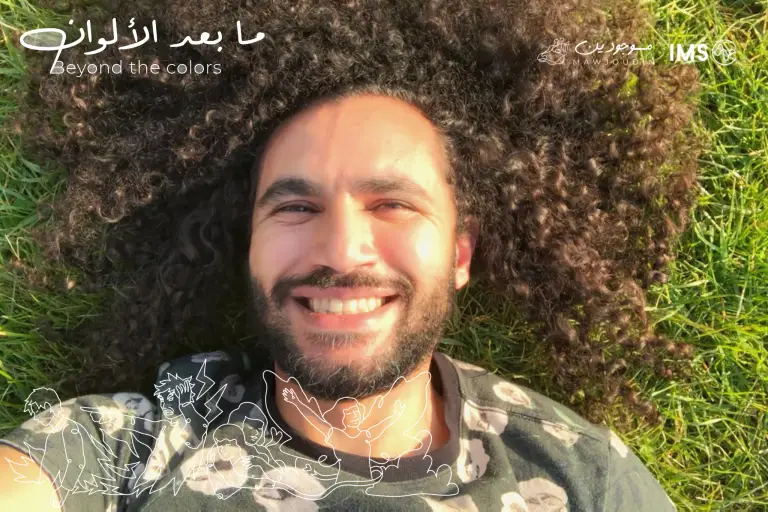

His cheerful personality and welcoming manner arouse interest, but above all encourage people to get to know him and find out more about his checkered life story. Mohamed speaks openly about "coming out of the wardrobe". The 39- year-old activist was willing to share this bittersweet part of his life with us.

“No worries about being called or introduced by whatever pronouns you want. (Smile)” The invitation was open for a non-gendered and spontaneous conversation. This exchange, at once painful and necessary, unfolds from one thing to the next, recounting a fragment of life, so short yet so shattered. It all began in the United Arab Emirates…

At first, the baby steps ...

“You can’t say that I had an unhappy childhood or adolescence. I grew up in a loving family cocoon, loved and surrounded, first and foremost, by my brothers and sisters and… especially by my parents.” Remembers Mohamed. He underlines a comfortable youthful existence, which could not in any way change… and yet.

In an era with very limited connectivity, and where the Internet was not as important as it is today, encounters, whether fortuitous or solid, were more spontaneous and went hand in hand with the discovery of oneself and one’s sexuality. This was well before the advent of the 2000s and all its upheavals. So, at just 16, Mohamed had no hesitation in telling his parents about his physical attraction to men… A confession that was immediately wiped away. “No doubt a form of denial on their part”. He comments, paraphrasing their reaction: “It’s probably just a bad phase, a short-lived period of discovery. It’ll pass! they said.” It was his very first coming-out and probably the least stormy. Little did Mohamed know that the worst was yet to come…

Thunderstorms on the horizon...

Indeed, he may not have known it at the time, but this primary revelation had just shaken his life to its very core. When he was just 17, he moved alone to Alexandria to pursue my medical studies at the University of Alexandria. Barely 6 months after his arrival, M. found himself entangled in a case of debauchery and was sentenced to 4 months in prison. It was an ordeal that severely damaged his ties with his parents.

“It was a very bad encounter that I had online. Dating websites were just emerging. “It was a meeting with a man to see each other and ask questions to explore a certain aspect of myself in a way, who turned out to be a cop, and who was stalking Queer and gay people online.” He remembers.

A context is necessary to better understand Queer life 22 years ago in Cairo…

In a large cosmopolitan capital, the Egyptian Queer community lived a hidden but fulfilling double community life. Meeting places, queer slang, mostly private parties. Dating websites made it easier to make meetings, chat rooms and other websites were all the rage. “It’s such a long time ago and it’s not making me any younger… Not a bit!” (Smiles). It’s an effervescence that occasionally gives rise to scandals, causing gossip and upsetting the Egyptian people on more than one occasion. He says: “My arrest happened so quickly and in this manner because of the rumors circulating about the presumed homosexuality of one of the sons of former President Hosni Mubarak and the nephew of one of the vice ministers of the interior at that time. The latter, who was publicly ‘outed’.” What people will say is pushing the authorities, once in charge, to use dirty methods and arbitrary arrests to suppress the community and dispel gossip.

We are also talking about the early 2000s, and Mohamed also recalls the “Queen Boat” affair, which at that time encouraged the authorities to toughen up the merciless witch hunt for people who were gay or suspected of being Gay or Queer. The tension hovered in a morass of stories that were created to divert public opinion. For a year and a half, the police authorities were mobilized to hunt down the LGBTQI++ community and M. was among dozens getting arrested. An ordeal that will transform his parents into his own jailers. We are in 2002, M, released from prison… still not an adult.

Hell lies at home!

“My parents gave me a hard time after I got out of prison and all they could think of was putting me through conversion therapy”. He recalls, with great lucidity and hindsight. Hell lies at home. His brothers and sisters found themselves completely unable to help him. Mohamed*, being the eldest, had to fend for himself. Mentally disturbed, he still aspired to a calm daily life, despite parental mistreatment, especially that of his mother, he recounts: “She went so far as to deprive me from eating, to isolate me, to deprive me of food and, much later, to call my friends to get them away from me. She was tyranny embodied! She was the one who mostly urged me to ‘be cured’”.

As the mother mistreated him, the father was indifferent; he observed all this mistreatment without reacting or intervening. Upon reaching the age of 22, Mohamed literally lived under death threats in his own family entourage. Fleeing had become a matter of life or death for him.

And then it was time to leave

The unprecedented violence inflicted by the parents was beyond comparison. He had to leave, but where to? For months, he would even starve. Then one day Mohamed took a few belongings with him, left the house, stopped a taxi without knowing where he was going… and finally found shelter at the house of a straight friend who took him in for a while and with whom he was “out”.

Mohamed adds: “A while after I left, my father called me to ask about me and try to talk some sense to me. He asked me questions about my future, whether I was a sex worker to earn a living… etc. He wanted me to come back on condition that I undergo conversion therapy, or to hide… but as far as I was concerned, it was out of the question for me to be subjected to this abuse or to pretend to be someone I’m not. My mother, on the other hand, still didn’t want me without a ‘change’. As if that were possible. So, it was down to them – both of them at a standstill! They started butting heads with each other right afterwards and as time went by… still in her furious madness, my mother started ordering my siblings to break off contact with me, which didn’t happen! In fact, we stayed close to each other.”

Remembering a detail along the way, Mohamed says that in the midst of the turmoil, and before leaving the family home, “My first love wanted me to live with him. But I refused because I wanted to stay with my family. That’s why we broke up. After the breakup, my violent problems started at home…I would have accepted if I’d known I was going to end up on the streets” (Smiles). Some friends in the community found it frightening to leave the house and wanted Mohamed to stay and “keep on pretending like them… but no, that was out of the question for me!” he proudly declares, with no regrets.

Mohamed is now 39 years old, and since what he calls his “3rd Coming Out”, he has made a path on his own, educated himself, finished his medical studies and devoted himself to the IT and administration sectors, alternating study and work, and teaching Arabic and German to foreigners. The IT sector and a number of civil society projects have enabled him to make a decent living.

The aftermath

After the 2011 revolution, his relationship with his parents eased… temporarily, after more than 5 years apart. “The revolution allowed people to talk, or at least to become aware. To accept and acknowledge a little social diversity. To include a few new values: tolerance, a taste for discussion, diversity, and inclusion. Hope began to emerge…”. He comments on this period of time.

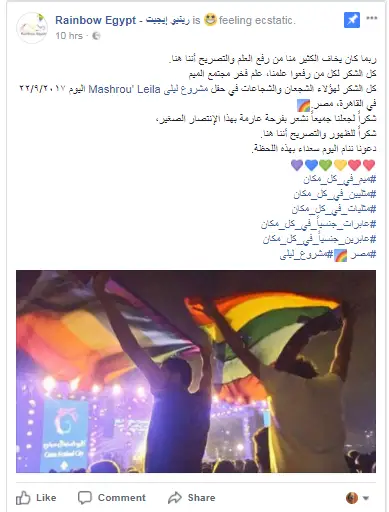

Until the umpteenth drama that will forever change M*’s life: the affair of the LGBTQI++ flags waved in a “Machrou3 Leila” concert in Egypt. He recalls: “In this affair, I expressed myself in a post that resonated at the highest political level and with the security and police authorities. It had become a danger for me to return. I was stuck in Lebanon for two months before finally requesting asylum in France on December 1st, 2017. Leaving the country had become a question of survival. Against my will, it had to be done. I have been a political refugee ever since.”

To the question: “Does he miss Cairo?” he answers… with difficulty. “At first, I was prone to fits of severe nostalgia. But I ended up accepting that I had the best life I wanted to have now, away from all the hassles, problems, pressure…I breathed, away from the country. Once I gained some distance, I realized just how much danger I was living in. Horrible! Unacceptable. All that is behind me now. I’ve changed my life. I’ve taken charge of it and I’m not coming back. If I had to leave, it’s clearly for the best, and if I come back, I’d be in the law’s crosshairs. I still can’t choose where to live. I breathe, I feel good, I have a stable, ordinary life. That’s enough for me: I don’t need a colourful or perfect life”. Mohamed replies, in some kind of resignation.

He opts for happiness and peace, despite the setbacks and the ups and downs. Avoiding pressure from society, family or living in the shadows… Anything but being someone else or playing a role. And he concludes: “Every Coming Out is unique. Who am I to give advice?”.